The Ancient Craft of Changing Potatoes into Premium Spirits

Liquor made from potatoes is a time-honored tradition that produces some of the world's smoothest, most distinctive spirits. Here's what you need to know:

Quick Answer: Making Potato Liquor

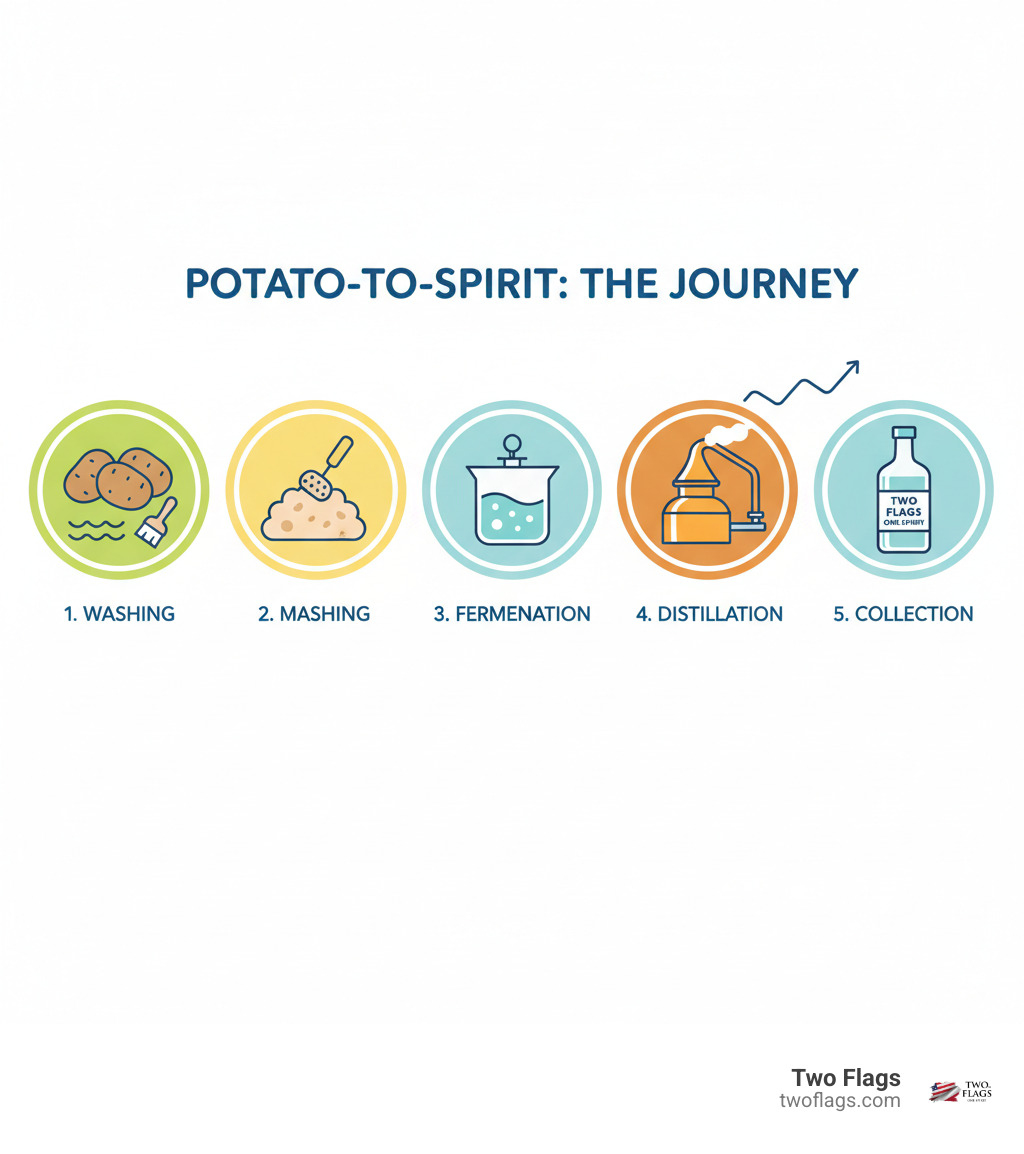

- Wash and boil 20 pounds of high-starch potatoes until soft

- Mash the potatoes and add malted barley to convert starches to sugar (at 150°F/66°C)

- Ferment the mixture with distiller's yeast for 7-14 days

- Distill the fermented wash, discarding the first 100ml (methanol) and collecting the "hearts"

- Filter and dilute to 40% ABV for drinking strength

The result is a creamy, silky-smooth spirit with a full-bodied mouthfeel that sets it apart from grain-based vodkas.

While only about 3% of vodka worldwide is made from potatoes today, this humble tuber has a rich 300-year history in spirit production. Swedish scientist Eva Ekeblad finded the process in the 18th century, and it became the bedrock of Polish vodka tradition.

The appeal is simple: potatoes create a naturally gluten-free spirit with a distinctive character that wheat or rye simply can't match. The extra starch requires more work to convert to sugar, but the payoff is worth it—a neutral spirit with subtle earthy notes and exceptional smoothness.

Making liquor from potatoes at home is challenging but rewarding. You'll need basic equipment (a large pot, fermentation bucket, and still), high-starch potatoes, malted barley for enzyme conversion, distiller's yeast, and patience. The process mirrors commercial production but on a smaller scale.

Important note: Home distillation is illegal in many countries without proper permits. Always check your local laws before attempting to make spirits.

I'm Sylwester Skóra, co-founder of Two Flags™ Vodka, where we honor Polish tradition by crafting ultra-premium liquor made from potatoes using time-tested methods. Our family's journey from Poland to America taught us that the best spirits come from respecting both heritage and quality. Let's explore how this ancient craft transforms simple potatoes into exceptional spirits.

From Tuber to Tipple: The History and Allure of Potato Spirits

The history of liquor made from potatoes reads like an unexpected adventure storyone that begins with a curious Swedish scientist and transforms the drinking culture of entire nations.

Picture Europe in the 18th century. Potatoes were still a relatively new crop, and most people saw them as nothing more than humble food for the table. Then along came Eva Ekeblad, a Swedish scientist who looked at these starchy tubers and saw something entirely different: the potential for exceptional spirits.

Around 300 years ago, Ekeblad finded that potatoes could be distilled into alcohol. This wasn't just an interesting experiment in a laboratoryit was a revelation that would reshape agriculture, industry, and social life across Northern and Eastern Europe. Suddenly, farmers had a valuable new use for their potato crops, and distillers had a fresh base ingredient to work with.

In Poland, our homeland, this findy took root in a profound way. The country's rich soil produced excellent high-starch potatoes, perfect for distillation. Polish distillers acceptd the tuber wholeheartedly, developing techniques that would be passed down through generations. Polish vodka tradition became synonymous with potato spirits, creating a legacy that continues today.

But Poland wasn't alone in its potato spirit enthusiasm. In Germany, distillers also acceptd the tuber. Germans had been experimenting with potato distillation as early as the 17th century, but things really took off in 1817 with the invention of the Pistorius still. This predecessor to modern column stills made potato distillation cheaper and more efficient. Unfortunately, the resulting flood of affordable spirits led to a period of widespread alcoholism that showed both the power and the danger of accessible spirits.

The rise of potato-based spirits wasn't just about availabilityit was about character. Distillers finded that potatoes created spirits with a distinctly different profile than grain-based alternatives. The extra work required to convert potato starch into fermentable sugars resulted in spirits with a creamy texture and full-bodied mouthfeel that set them apart.

Today, liquor made from potatoes holds a unique place in global vodka history, even if its market share has shrunk. Only about three percent of vodka sold worldwide comes from potatoes now. The process is more complex and less cost-effective than grain-based production, which has led many producers to abandon the practice entirely.

But here's the beautiful irony: that very scarcity makes potato spirits more special. For those who appreciate tradition, craftsmanship, and a spirit with genuine character, potato vodka represents something increasingly rare in our modern worlda connection to centuries-old methods and the authentic taste that comes from doing things the harder, better way.

From Eva Ekeblad's pioneering work to the traditional Polish distilleries that still honor these methods today, the potato has earned its place in spirits history. It's a testament to human ingenuitytaking a humble vegetable and changing it into something extraordinary.

The Essential Toolkit and Ingredients

Before you can start making your own liquor made from potatoes, you'll need to assemble the right equipment and gather quality ingredients. Think of it like preparing for any significant cooking project—having everything ready before you begin makes the entire process smoother and more enjoyable.

The star of the show is, of course, potatoes. But not just any potatoes will do. You want high-starch varieties like Russets, Yukon Golds, or Kennebecs. These varieties contain more starch, which ultimately converts to more alcohol. Plan on using around 20 pounds for a decent-sized batch. That might sound like a lot, but remember—you're making spirits, not mashed potatoes for dinner!

Next comes malted barley, which might seem like an odd addition when you're making liquor made from potatoes. Here's why it's essential: malted barley contains natural enzymes called amylase that break down those potato starches into fermentable sugars. Without this conversion, your yeast would have nothing to eat, and you'd end up with potato soup instead of vodka. You'll need approximately 2 pounds of crushed malted barley for every 20 pounds of potatoes.

Distiller's yeast is another critical ingredient. This isn't the same yeast you'd use for baking bread. Distiller's yeast is specifically bred to tolerate higher alcohol levels and work efficiently in converting sugars to alcohol. It's the workhorse that transforms your potato mash into something worth distilling.

Don't overlook the importance of water. Clean, purified water matters throughout the entire process—from cooking your potatoes to diluting your final spirit. Tap water with high mineral content or chlorine can affect both fermentation and flavor.

Now for the equipment. You'll need a large pot—at least 5-gallon capacity—for boiling and mashing your potatoes. This is where the magic begins, so make sure it's sturdy and can handle extended heating.

A fermentation bucket (around 7.5-gallon capacity for a 5-gallon mash) serves as the vessel where your mash transforms into alcohol. It should be food-grade plastic with a tight-fitting lid. You'll drill a hole in that lid for an airlock, which allows carbon dioxide to escape during fermentation while keeping unwanted bacteria and wild yeast out.

Temperature control is absolutely crucial, so a good thermometer is non-negotiable. During starch conversion, you need to maintain temperatures around 150°F (66°C), and when pitching yeast, precision matters. A few degrees in either direction can make the difference between success and disappointment.

A hydrometer helps you track fermentation progress by measuring specific gravity—essentially how much sugar remains in your mash. This simple tool tells you when fermentation is complete and helps estimate your alcohol content.

When fermentation finishes, you'll use a siphon or auto-siphon to transfer the liquid (now called "wash") away from the sediment that settles at the bottom. This step, called racking, prevents off-flavors from making it into your final product.

The heart of the operation is your still—either a pot still or reflux still. A pot still is simpler and produces spirits with more character, while a reflux still offers higher purity and a more neutral spirit. Both work beautifully for potato vodka, though reflux stills better match the clean profile of premium commercial products.

You'll also need collecting vessels for catching your distillate, and an alcoholmeter to measure the final ABV (alcohol by volume) of your spirit. While optional, a carbon filter significantly improves the smoothness and purity of your finished vodka.

Gathering these tools and ingredients is your first real step toward understanding what goes into crafting premium liquor made from potatoes. It's the same attention to quality ingredients and proper equipment that we use at Two Flags™ Vodka—because whether you're making spirits in your home or at a commercial distillery, the fundamentals remain the same.

The Step-by-Step Guide to Making Liquor from Potatoes

Now comes the exciting part—changing those humble spuds into smooth, crystal-clear spirit. Making liquor made from potatoes is a multi-day journey that requires patience, attention to detail, and respect for the process. Each step builds on the last, so let's walk through this together, just as distillers have done for centuries.

Preparing the Potato Mash: The First Crucial Step

Everything starts with properly preparing your potatoes. This isn't just about cooking them—it's about open uping the starches hidden inside each tuber so they can eventually become alcohol.

Begin by washing your potatoes thoroughly. You'll need about 20 pounds of high-starch varieties like Russets or Yukon Golds. Here's an important tip: don't peel them. Much of the starch we're after sits just beneath the skin, and we want every bit of it.

Next comes boiling. Place your washed potatoes in your large pot, cover them with water, and boil for about an hour until they're very soft. You should be able to easily pierce them with a fork. This process is called gelatinization, and it's absolutely crucial. The heat breaks down the potato's cell walls, making those starches accessible for the next step.

Once your potatoes are tender, drain most of the water (but keep some—we'll need it). Now it's time for mashing. Mash those potatoes thoroughly, adding back enough hot water to create a thick soup-like consistency. You're aiming for about 5 to 6 gallons total. For an even smoother mash, you can use a food processor or immersion blender to really liquidize everything.

Here's where the science gets interesting. Let your mash cool to around 150°F (66°C)—this temperature is critical. Too hot, and you'll destroy the enzymes we're about to introduce; too cool, and they won't work efficiently. At this perfect temperature, add about 2 pounds of crushed malted barley.

The malted barley contains amylase enzymes that act like tiny molecular scissors, cutting complex potato starches into simple, fermentable sugars. Maintain that 150°F temperature for about two hours, stirring occasionally. This is called starch conversion, and it's the bridge between raw potatoes and drinkable spirit.

If you want to boost your yield, you can add up to 2 kilograms of sugar during this stage. While traditionalists might skip this step, it significantly increases alcohol production. Sugar typically yields about 1 liter of 70% alcohol per kilogram, while potatoes alone might give you only about 2 liters of 50% vodka. The choice depends on whether you're prioritizing authenticity or efficiency.

For more insights into the foundational steps of spirit creation, check out our detailed guide: Vodka's Journey: A Step-by-Step Guide to How it's Crafted.

Fermentation: Turning Sugars into Alcohol

With your sugar-rich potato mash ready, it's time to introduce the real workers: yeast. These microscopic organisms will feast on the sugars and produce alcohol as a byproduct. It's nature's alchemy at its finest.

First, you'll need to cool the mash down to a yeast-friendly temperature. Yeast is particular—too hot and you'll kill it, too cold and it won't work efficiently. Aim for somewhere between 65-77°F (18-25°C). You can speed up cooling with an ice bath, but make sure everything stays sanitary.

While your mash cools, prepare your distiller's yeast according to the package instructions. When the mash reaches about 80°F (27°C), it's time to pitch the yeast—that's distiller-speak for adding it to your mash. Before pitching, give the liquid a gentle stir to incorporate some air. This helps the yeast get off to a strong start.

Transfer everything to your fermentation bucket, secure the lid, and install your airlock. This clever device allows carbon dioxide (the other byproduct of fermentation) to escape while keeping oxygen and contaminants out. Make sure you've left enough headspace—the mash can foam up quite a bit, especially in the first few days.

Fermentation time typically runs 7 to 14 days. You'll know things are working when you see bubbles moving through the airlock. Some distillers like to stir the mash daily to reintegrate any foam that forms on top. This is optional but can help keep fermentation moving smoothly.

How do you know when fermentation is complete? The airlock will stop bubbling actively, and if you taste the liquid (carefully!), it should no longer taste sweet. For a more scientific approach, use your hydrometer to measure specific gravity. When the reading stays stable for a couple of days, fermentation is done.

Now comes racking—letting the liquid settle for 24-48 hours, then carefully siphoning the clear liquid (now called "wash") off the sediment at the bottom. This sediment is spent yeast and potato solids, and we don't want it in our still. Leaving it behind prevents off-flavors from contaminating our final spirit.

Distillation: Purifying the Spirit

Distillation is where your patience pays off. This is the process that separates alcohol from water and concentrates it into the smooth spirit you're after. It's also where safety becomes absolutely critical.

Before you begin, double-check that your still is properly assembled, with no leaks and all connections tight. Always operate in a well-ventilated area, away from open flames. Alcohol vapor is flammable, and we're taking no chances.

Transfer your wash into the still and begin heating slowly. Alcohol boils at around 173°F (78°C), lower than water's 212°F (100°C), so the alcohol vapors rise first. This is the principle that makes distillation work.

As liquid begins dripping from your condenser, you'll need to make the cuts—separating the distillate into different fractions. This is arguably the most important skill in distillation.

The first portion, called foreshots, is about 100ml (roughly two ounces per five gallons of wash). This contains methanol and other volatile compounds that are dangerous to consume. Discard this completely. Methanol can cause blindness and even death, so there's no room for shortcuts here.

After the foreshots come the hearts—the pure, smooth, desirable portion of your spirit. This is what you're after. Collect the hearts until the alcohol content drops noticeably or you detect off-flavors. These off-flavors come from fusel oils, heavier alcohols that emerge later in the run.

Finally, the tails arrive. This final portion contains heavier alcohols and less pleasant flavors. Most distillers stop collecting when the distillate falls below 30% ABV or starts tasting "funny." You can discard the tails or save them for redistillation in your next batch.

For truly exceptional liquor made from potatoes, consider multiple distillations. While modern reflux stills can achieve high purity in one run, traditional methods often involve three or more distillations. Each run removes more impurities and creates a smoother, more neutral spirit. If your still has copper components, that's a bonus—copper naturally removes sulfur compounds that can create off-flavors.

To understand more about what makes a neutral spirit truly exceptional, explore our article: Beyond the Buzz: Understanding Neutral Spirits in Your Favorite Drinks.

After distillation, measure your alcohol content with an alcoholmeter (calibrated at 68°F or 20°C). You'll likely have something quite strong—perhaps 70% ABV or higher. Dilute it with purified water to drinking strength, typically 40% ABV (80 proof). Many distillers also run their spirit through activated carbon filtration for additional smoothness.

The result? A handcrafted spirit that carries the subtle character of its potato origins—creamy, smooth, and entirely unique.

The Art of Finishing: Why Potato Spirits Stand Out

After we've distilled our liquor made from potatoes, something magical happens. This is where the unique personality of potato spirits truly reveals itself, setting them apart in a crowded spirits market.

The finishing touches—filtration and dilution to the perfect drinking strength—are what transform a raw distillate into a premium vodka. But even before these final steps, potato spirits already possess qualities that make them special.

The Unique Characteristics of Liquor Made from Potatoes

What makes liquor made from potatoes so distinctive? The answer lies in its remarkable texture and flavor profile.

The most celebrated characteristic is the creamy texture that potato vodka is famous for. This isn't marketing speak—it's a genuine sensory experience. The slight creaminess translates into a silky-smooth taste that coats your palate in the most luxurious way. It's like comparing velvet to cotton; both are soft, but one just feels more refined.

Beyond texture, potato spirits offer subtle earthy notes that grain vodkas simply can't replicate. Where grain-based vodkas might lean crisp or even peppery, potato vodka tends toward a full-bodied mouthfeel with hints of sweetness, vanilla, or even nutty undertones. Some freshly distilled potato spirits have been described as having an intriguing orange-creamsicle quality—though this mellows with time and filtration.

This rich, smooth character is exactly why we're so passionate about crafting Two Flags™ vodka from potatoes. We believe this depth and smoothness represents vodka at its finest. To truly appreciate what separates exceptional vodka from ordinary, explore: Sip Smarter: Discovering What Good Vodka Really Means.

Here's how potato vodka compares to grain-based spirits:

| Feature | Potato Vodka | Grain Vodka |

|---|---|---|

| Base Ingredient | High-starch potatoes | Wheat, rye, or corn |

| Flavor Profile | Subtle earthy notes, hints of sweetness, vanilla, or nuttiness | Crisp, clean, sometimes peppery |

| Mouthfeel | Creamy, silky-smooth, full-bodied | Lighter, more neutral |

| Common Perception | Premium, traditional, artisanal | Standard, widely available |

Is Liquor Made from Potatoes Gluten-Free?

Here's great news for anyone with dietary restrictions: liquor made from potatoes is naturally gluten-free. Since potatoes contain no gluten whatsoever, the resulting spirit is safe for those with celiac disease or gluten sensitivity.

This makes potato vodka an excellent choice for anyone avoiding gluten, whether for medical reasons or personal preference. Unlike grain-based vodkas, which start with gluten-containing ingredients (even though most of the gluten proteins are removed during distillation), potato vodka never encounters gluten in the first place.

At Two Flags™, we take this a step further. Our vodka is not only gluten-free but also organic and GMO-free, giving you a spirit that's as clean and pure as possible. We believe your choices matter—not just for taste, but for your health and values too. Learn more about why quality ingredients make all the difference: The Organic Advantage: Why Your Choices Make a Difference.

The combination of being celiac-safe, naturally pure, and crafted with traditional methods makes potato vodka a standout choice for discerning drinkers who want both exceptional taste and peace of mind.

Zostaw komentarz

Ta strona jest chroniona przez hCaptcha i obowiązują na niej Polityka prywatności i Warunki korzystania z usługi serwisu hCaptcha.